The Three Flags Highway (US Hwy 395) stretches 1300 mi. (2100 km.) virtually from the Canada border south, along the backbone of the USA’s western mountains nearly touching the Mexico frontier. It must surely be one of the most sweeping and storied stretches of road in America while escaping almost entirely the monotony of her interstates. Strung along the California section of this necklace lie Yosemite National Park, Lake Tahoe, premier skiing country around Mammoth Lakes, Death Valley, and Mt. Whitney while tiptoeing just above the highway is the renowned Pacific Crest Scenic Hiking Trail.

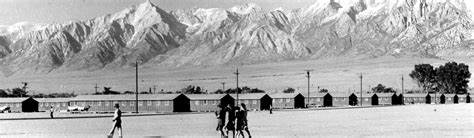

Americans after the outbreak of WW II. It came to house 10,000 internees mostly from the Los Angeles area. The

barracks consisted of pine planking overlaid with tar paper. Memoirs of the time describe ever present high wind and dust and bitter cold winters. Baseball became a passion for many, while gardens sprang up in available corners of the camp. During its 3 1/2 years of operation 188 weddings took place and 541 children were born. Survivors and descendants of these families now gather annually at the site for the Manzanar Pilgrimage at the end of April.

photo credit: National Park Service

So stunning are these vistas and quaint, western towns, it would be entirely possible to miss a non-descript sign for ‘Manzanar’, as we nearly did one winter while traveling south through the Owens Valley. The sign flashed by striking a faint bell somewhere, though we sailed on south, high desert on our left and majestic ridges on the right. That night I began searching for the source of that faint ringing I’d heard. And then the story came to light. Manzanar: a camp where Japanese American families had been interned when war broke out in the Pacific in WW II, ten thousand of them hustled behind barbed wire, under machine-gun guard towers and search lights. An American gulag.

That story, lending no luster to American history, summoned up the memory of a conversation I’d once had on the far side of the world. A colleague, soon to return to North America after years abroad, mused about his to-do list once back home. He’d grown up in suburban California, he said, where their family home included an elegant upright piano that nourished the family’s love of music. Only later did he learn, to much distress, that the piano came to his family from some neighbors – as it turns out, Japanese Americans – who sold it when they were ordered to report for internment at Manzanar. His grandparents had bought the piano on fire-sale terms as war dominated newspaper headlines.

Suddenly he looked back on his childhood full of music with startled, searching eyes. How could his innocent love of music – the lullabies, the folk melodies, the lieder and waltzes – have cost others so dear? How was it that this beauty could resound even into adulthood without a hint of the lament behind it? He told me that he had this ambition on his return: to find the descendants of that family and to acknowledge the injustice they’d suffered which had, ironically, so enriched him.

I never learned the upshot of his quest. It would deserve a telling. But reflection on his story leads to awareness that it is a tiny part of a much larger mosaic: that there is a faint tolling bell behind some of what comes to us as elegant blessing. It is not a misguided thing, if that be true, to lead a life’s to-do list with the ambition of acquainting ourselves with that hidden loss and making what amends are yet possible. Such, it turns out, is the source of the most beguiling music.

And that’s how far it is to Manzanar.

*This line has the faint cadence of a Christmas poem, ‘How Far Is It To Bethlehem?’, from the hand of Frances Chesterton, poet and playwright.

Jonathan: a shout out from Santa Cruz Bolivia! First: Thanks for the whole series (which your sis Sara hooked me up to on her visit with us).

I only met you once at the “Menno-meet” in Atlanta but I still remember the witness of your faith stories.

About this one: ever read Lawson Fusao Inada’s poetry? He was a child at Manzanar and it colored everything he wrote, even after becoming Oregon poet laureate. I heard him read his work once and still remember his focused calm.

Hope to meet you again on some path…

Hello, Wendell and all! Such a pleasure to reconnect – and from your current perch back in Bolivia! I had, indeed, noticed a burst of interest from Bolivia registered by my blog metrics. Though I treasure readers in many remote corners of the globe, having friends in Santa Cruz is noteworthy! And thanks for the nudge to go find the poet, Inada! That has led me to a trove of material that further opens up the world of the Manzanar experience. It is a reminder to me that where disgraceful wrongs take hold, something noble and rare often rises to match it. And the Amstutz family story is enrolled there.