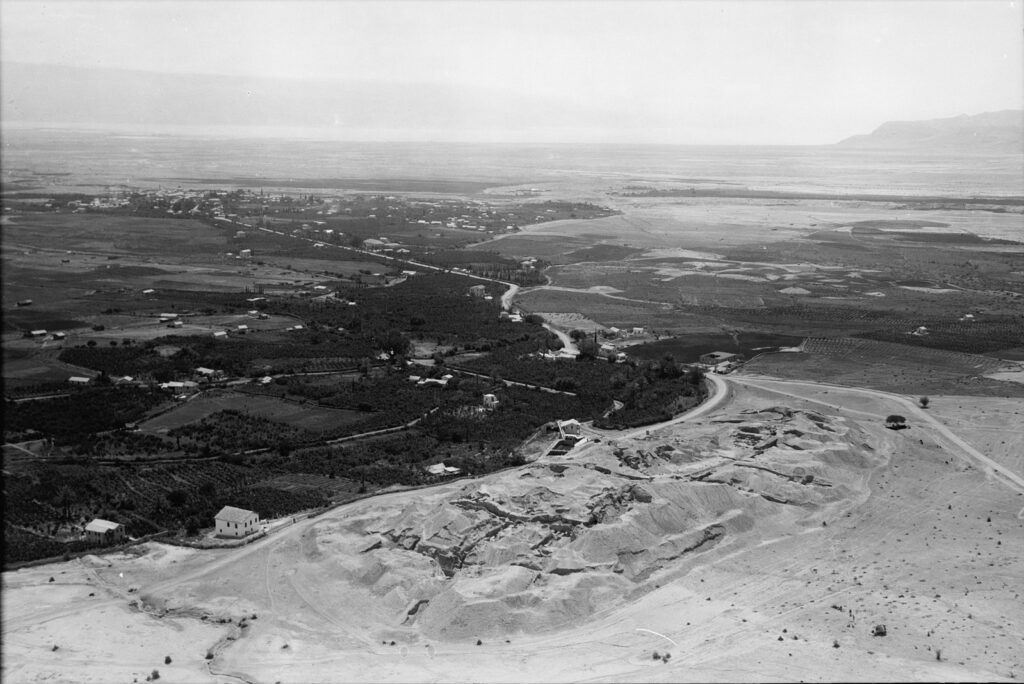

A modern highway winds west from the palms of Jericho – reputedly the oldest continuously inhabited city on earth – upwards into parched hills. But there is an alternative route: a pilgrim trail that disappears up the Wadi Qelt beyond the city ruins. A rise brings into view the shimmers – was that a whiff of sulfur? – of the Dead Sea to the south and to the northeast, a green trace of the Jordan River. Though dotted with a few shrines to desert ascetics, the track up this extraordinary defile is free of clutter. Naked rock and heat still rule, while the ravine seems to echo with story: the sighs of prophets and hermits, fugitive whispers, pilgrim chants and the cry of ravens. Along this byway some soul of sacred country lingers.

The trail crests the highland and there before you lie the ramparts, the mosques, the shrines, the landmarks – and now the scattered suburbs – of Jerusalem. We drove to a bus stand at the Damascus Gate where we met our host, Solomon Mattar, a Palestinian, who led us to pilgrim accommodation down a cobblestone alley just footsteps beyond the Gate. A kindly host, a supper of flat bread and lamb on the street, grateful chatter at arrival, a shower and the sleep of the dead – such are the graces of pilgrim life.

But there is a wistful coda to this brief encounter on our travels. The annals of the city, like its pilgrim trails, seldom lack for turbulence and suffering. Not long after our passing, Mr. Mattar, prominent for serving as custodian of the Garden Tomb, together with his family, were caught up in all-out war with shelling and indiscriminate firing in the streets. He went to the gate of the property it seems to plead with the combatants, got caught in crossfire, and lost his life on the Nablus Road where he had long welcomed throngs of pilgrims.

Morning brought us dilemmas of how to allot our limited time in the city: Al Aqsa mosque, the Western Wall, the via Dolorosa, the Church of the Holy Sepulcher, the Shrine of the Book, Yad Vashem … the list was endless, worthy and impossible. But off those well-trod paths there awaited indelible experiences, enduring as the tattoos pilgrims once sought to confirm fulfillment of their vows. Beneath the clamor and kitsch, for instance, lay Hezekiah’s Tunnel. While long-ago empires clashed around a city that held its breath in expectation of a siege, the inhabitants of Jerusalem chiseled a tunnel through solid rock bringing within its walls a supply of water from a perennial spring. Two teams worked from opposite ends of the proposed shaft, a distance of over 500 meters with a necessary gradient of 30 cm (1 ft.). Working by torch light, the teams met seamlessly at the mid-point using nothing but iron tools.

Feeling our way along this tunnel in darkness with flowing water up to the thighs, bending low to pass the choke points, seemed like a journey into raw and desperate times that required dead reckoning shorn of all ornament while destiny hung in the balances.

Now, there’s an unvarnished passage deserving of a shrine. Chant a paean. Light a candle there in the darkness in memory of the nameless who hammered at the rockface while tyranny unfurled its banners around the walls.

In pursuit of such corners, we found ourselves stirred and enriched, but well adrift of the beaten trail.

*In the summer of 1965, four school chums from Woodstock School in India, including writer Jonathan Larson, joined a handful of others for an epic road journey from Karachi, Pakistan to Rotterdam, Netherlands. Dubbed here as the Mother of All Road Trips, its itinerary of 8000 kilometers (5000 miles) in a Volkswagen sedan passed through some of the most dramatic topography on the planet, crossing a panoply of peoples, histories and cultures. A rising tide of conflict – even war – along the route would soon make such travels nearly unthinkable.

Thank you.

Thanks,

Jonathan