There is hardly any place name, with the possible exception of ‘Shangri-La’, that is quite so evocative as ‘Mandalay’. Nearly all of its associations for the West are Kipling-esque ‘images of oriental kingdoms and tropical splendor’*. Dozens of book titles, songs and hotel names have ridden the crest of those images to fame and riches. Today, Mandalay dreams the world will come in search of that romance.

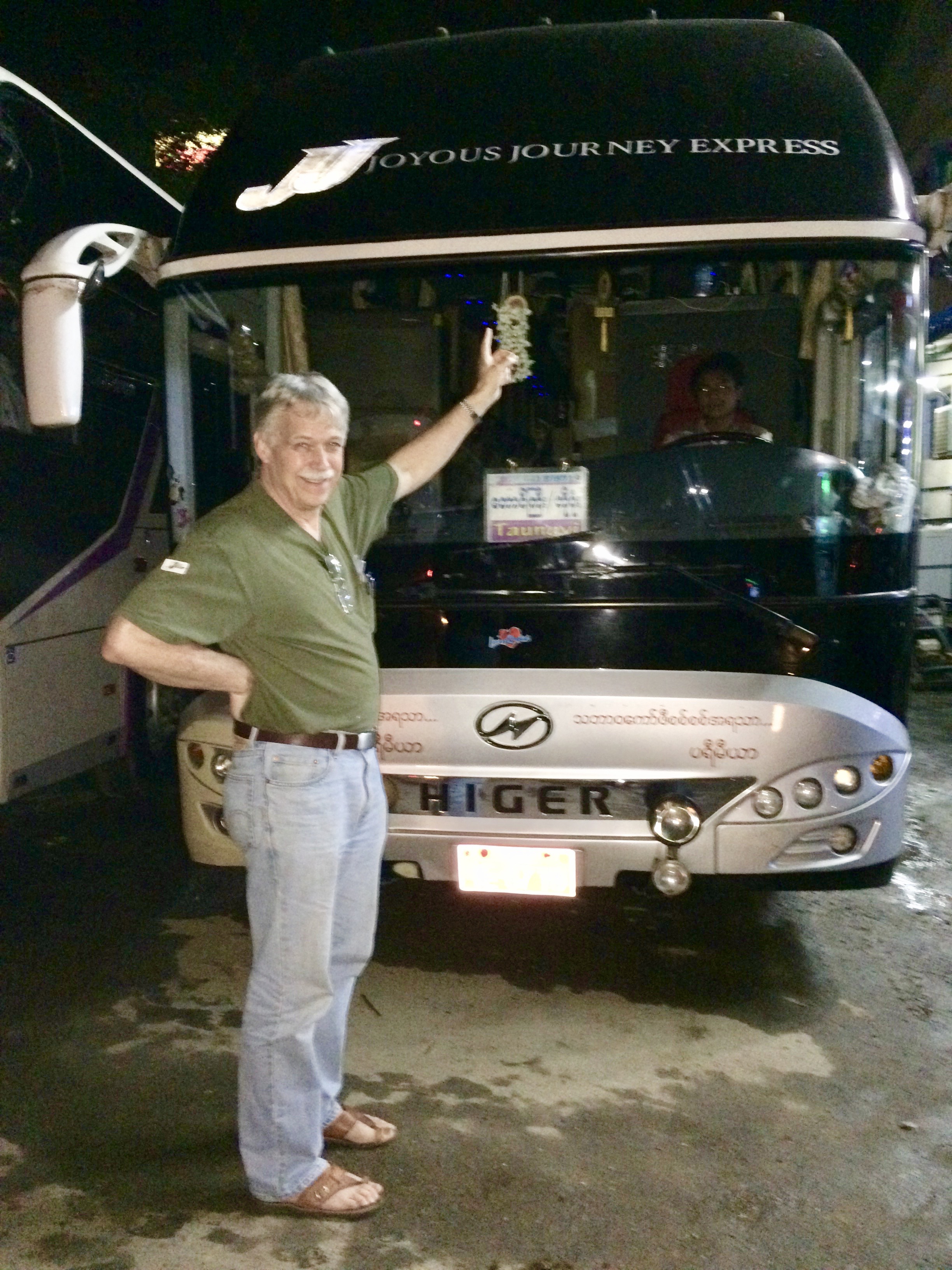

The Joyful Journey Express night bus from Yangon will take you there. Straight up Myanmar’s central valley, the highway runs, as though some army general laid a ruler on the map and barked, “Build it there.” What is striking about this journey are the swatches of darkness, hour after hour, without evidence of a single light, kerosene lantern or even candle – certainly no ‘flying fish’ – though traveling up one of the world’s richest river valleys. As I peer out into that darkness, a winter rain sets in. The driver presses on despite disabled windshield wipers. A loop of Tom and Jerry cartoons cycles through as onboard entertainment.

I am left to imagine on my own what is sleeping out there in the sodden night: the pagodas, bamboo groves, villages and rice paddies. The betel nut palms, the schools, the jack fruit and mango trees.

The bus pulls briefly in to the neon glare of Naypyidaw, Myanmar’s planned capital, a political work in progress. Lucky too, since the on-board toilet, like the wipers, is out of commission. A refreshment stand offers midnight 7-Up and Sunkist soda, and cake in impregnable cellophane wrappers. A potted plant doubles as a spittoon.

Finally, the JJ Express draws into Mandalay while the city sleeps in a rainy dawn. In the pale light, a sparrow perched on a cornice chatters a welcome. And backlit against the eastern sky a forest of cranes hangs over a city that would rather be known for its palaces and pagodas. A short taxi ride brings us to the Royal City Hotel from where we venture out to explore the fabled riches of Mandalay, a city with music in its name: the Amarapura (‘city of immortality’) monastery where a thousand robed monks walk solemnly through a lunch line as tourists jostle for camera advantage, the evening river full of pleasure boats, a replica palace erected on the ashes of calamity, pagodas marking the prominence of this city in the firmament of Theravada Buddhism and a procession of sequined horses and gilded bullock carts bearing families to appointed rituals.

But it is also this fountainhead of Buddhist learning that has given rise to the angry preaching of the monk, Ashin Wirathu, and his 969 movement that has brought suffering to the Rohingya and to Muslims across Myanmar some of whom I met in this city of dreams.

The story that lingers most insistently with me, though, I heard at rooftop breakfast when we sat with a traveler from the UK. She recalled having come to south India in the winter of 2004 to study yoga when that great wave swept in to their seaside hamlet. As the tsunami broke in fury on the village, she and her fellow students from abroad were rushed by their Indian hosts to the only two-storey concrete structure in the vicinity. From that vantage point she and a handful of foreigners gazed in horror as the power of the deep worked its rage upon the inhabitants of her village. Days passed before she was able to descend from safety to catch a bus out of the shattered coast, to assure her distant family that she had survived only through the kindness of villagers who themselves vanished into the sea.

Her eyes flicker with the memories. And not just of the pitiless power of nature. She wonders why her life was thought to be worthy of that second floor, when so many others were consigned to terra not-so-firma. Was this an extraordinary ethic of hospitality, or was it because of some insidious hierarchy she had pledged her life to overcome? And did she, in that moment, come face to face with an overwhelming truth that holds us all in some invisible grip?

That unflinching self-questioning was to me the equal of the most beguiling pagoda in the Irrawaddy valley.

*Michael Wesley, literary critic

I have but a universal observation and comment. Your TRAIPSE articles provide a picture which perspective the masses would /should want to see. You have managed again to take me on a trip to yonder places I could not have imagined but through your capacity to see and describe – encompassed within your descriptive writing style that supersedes any other I have ever read. Carry on my Friend; I will anticipate the sequels to his edition of TRAIPSE.

Hello, Harry! My long ago traveling companion in the Kalahari! It amazes me that simple words on a page can occasion journey in others. To travel in body is a blessing, to be sure. But to travel in heart and in sympathy with others, is beyond rare. An exquisite thing! Someone has said that story is how we wander the paths of eternity. That’s the real ‘Traipse’, mon cher!