They’re up there still. Hundreds of tents pitched in the rubble field at base camp on Everest. Climbers – some, at best bricoleurs – and their Sherpa guides wait for that window of clear days before the monsoon that offers some chance of summiting the mother of all mountains, Chomolungma, 29,035’ of rock, icefall, crevasses, thin air, majesty and a vista to die for.

That crowning reward, as hundreds have found to their dismay, reigns in what climbers call the ‘death zone’. There are, of course, the harshest of elements. But above 26,000 ft. (8,000 meters) the human body itself, deprived of sufficient oxygen, begins to break down. Fatigue sets in together with numbness and tingling of extremities. Then, the fight with nausea, vertigo and lack of sleep. But none of these physical effects is more pernicious than what happens to the functioning of the human brain. Beyond cracking headaches there may follow confusion, hallucination and breakdown in judgement, an inability to assess risk and read conditions. Unaddressed, all of that can entrain shock and death.*

That setting of extremis is the subject of alpine fascination and lore, with reverence reserved for those who face the death zone defiant, un-buttressed by modern technology or supplementary oxygen, even alone. Wherever climbers gather to swap knowledge of mountain routes and exploits, survival in that death zone is a lingering, if reluctant, theme.

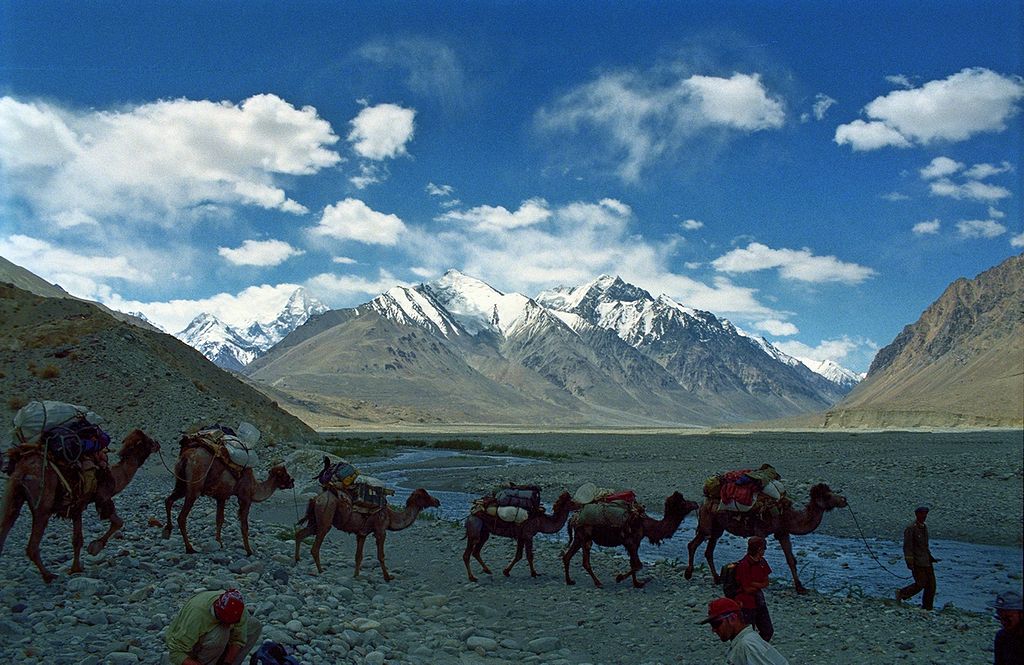

One such community clusters at Jackson Hole (WY), and especially Jenny Lake, lying at the foot of the Tetons. I once warmed myself by those campfires, tented next to a mountain man who knew his way around a jug of Mogen David. This, they say, was the proving ground for Paul Petzoldt, a godfather of American mountaineering who is said to have scaled the Grand Teton in cowboy boots as a stripling. Having won a colorful reputation for derring-do and determination, he agreed to join the first American expedition to explore K2 (28,251 Ft.) in 1938. Though ranked behind Everest in altitude, most acknowledge that K2 on the Pakistan-China border is the more difficult climb.

Those who later came under Petzoldt’s mentorship at NOLS (National Outdoor Leadership School, WY.) recall him telling the following story to impress upon his young charges the strange effects of the death zone. After the expenditure of great sums of money, after months of ship travel, preparation, and trekking into the Karakoram, when the time came to reconnoiter approaches to the K2 summit, he and another climber were chosen. The plan was to ascend as far as possible, then to bivouac and return the following day. The twosome, without oxygen, made fair progress and overnighted beneath the summit. But that evening they had a quarrel over what to do with the odd-number sardine in a can they had opened for supper. The many sensible ways to resolve this disagreement in normal circumstances eluded them in the rarified air. They retired for the night in foul spirits.

The next morning the weather had turned. But not their sour mood. Whether they should push on for the summit in the rising wind, once a possibility, now became a matter of contention. Petzoldt argued that the summit was still within reach, but his partner demurred saying they had surveyed the routes and should now retrace their steps. Unable to go on alone Petzoldt, together with his companion, descended to camp. The book account of the expedition (‘Five Miles High’) maintains that the whole effort was a resounding success having met all its objectives without loss of life. But Petzoldt wanted his trainees to know that a rare opportunity had been lost in a sardine can and in the oxygen-starved brains of two seasoned climbers.

This twist in an epic story is nowhere recorded in journals or books from the time. It may well be a scrap of hallucination brought back from the ragged edge of human endeavor. But it has a useful ring of truth as insight into our own flaws – yes, even in oxygen-rich environments: that we are known, too, in duress for taking momentary leave of moral bearings, for losing sight of the loftiest landmarks, the Himalayas of the heart.

*Some researchers argue that groups indigenous to high altitude – e.g. in Bolivia and Tibet – are resistant to the full effects of the death zone. Kami Rita, a Nepali Sherpa guide, has ascended Everest 24 times on the strength of a physique genetically adapted to high-altitude environs. Most climbers do allow for adaptation to high altitude (by one estimate, taking nearly 46 days for the body to adapt to 13,000 ft. of altitude). Reinhold Messner, legendary Italian alpinist with a purist approach, climbed Everest solo and without oxygen supply.

Your writing is always world-and-spirit-expanding. Today your name came up in conversation during our Care Group excursion as Aden Frey remembered your important leadership in Congo/Zaire. Impact continues…

Ron

Hello, Ron, Aden and all! An inspiration to think that you are checking in here on ‘Traipse’. In so many ways, those years in the Congo backcountry became for us the measure of what is worth attempting with modest gifts and powers. And keeping company with a coterie of aspiring volunteers like you all has continued to buoy us across the years! Be well! Jonathan