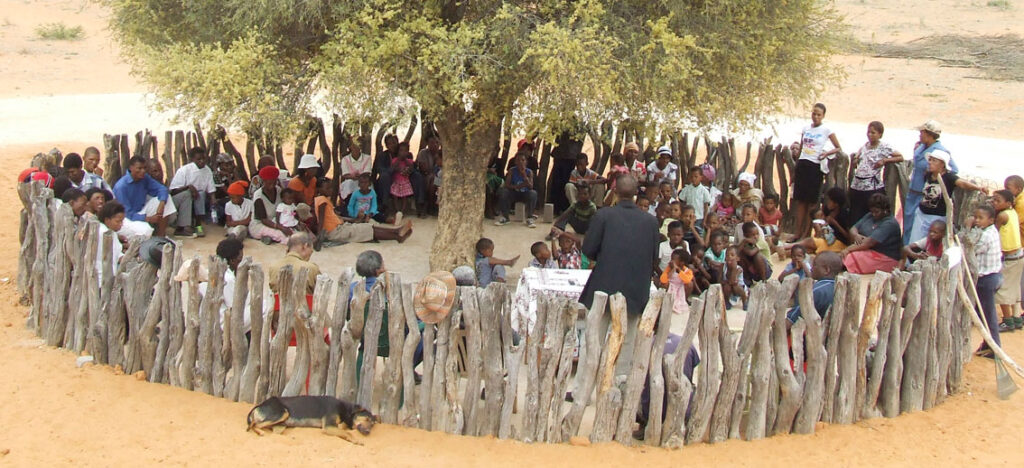

I sat listening in the courtyard of an elderly friend in the ramshackle outskirts of a Kalahari town. He was giving his account of the origins of the HIV pandemic. It went something like this:

HIV has come to our country by design of ill-willed foreigners*. We know that diseases native to this part of Africa all find their cure in the wilds of our customary lands. But this illness has no such remedy. Therefore, it has come from elsewhere. And it seems clear what purpose this affliction is supposed to achieve. It is intended to make us powerless who have been masters of these parts from ancient times. Unable to defend our health with our own wisdom and means, we are thus enslaved to purveyors of Western medicine. So, we are impoverished twice. First, the disease breaks us down bodily, humiliating us, and then it leaves us penniless after we pay for foreign remedies.

He said this with earnest. Even a touch of anger, an anger that certainly arose also from the larger truth that though born into a family of some renown, modernity had assigned him a shack well away from the towers built by diamonds and gold.

Though my friend’s view was widely shared by traditional people, it could not calm a fevered search for local answers most intensely among spiritual healers and doctors, especially since the symptoms of AIDS (like some other viral pandemics) mimicked familiar African disorders. The mass media, the bus stations, taxi stands and market places teemed with lurid stories of these traditional doctors. In one conversation, I heard tell of a wonderworker in the shadows of Great Zimbabwe, another holding sway on the shores of Lake Malawi, and yet another in the rain forest of the Congo whose feats had outshone them all. (I did not reveal we had spent three years teaching in that very region without ever encountering such a brilliant healer.) But it seemed clear that the more remote and exotic a healer’s place, the more potent the powers to set things aright.

But my most memorable encounter in the midst of pandemic suffering, desperation and helplessness came under the eaves of a Kalahari homestead with a widow named Mma Chabe, ‘Mother of the Nation’. However expansive such a name, there was no pretension in her shy welcome. She set out a folding chair for me as children scampered about a sun-drenched courtyard. Hers is a pandemic story of rare fragrance – and healing. I propose to tell it in my following post.

*Among the many parallels in our own pandemic experience must certainly be populist resentment over China as source of the Coronavirus. We, too, find consolation in laying the onus of our troubles at the doorway of others.

And yet again, conspiracy theories swirl about, covering the spectrum: diabolical foreign plots, divine chastisement; and on and on. Thanks for the much needed perspective, JP.

Hey, Mike! Good of you to respond! How nimble of you to catch the parallel threads! Wealth and education seem to alter very little our natural reflexes. The following story will also show how moral courage resides also in byway communities that have been left to their own devices. Gracias!

As you know too well, Rra Marang – ours is a highly immune suppressed population and the imagination of the impact of novel coronavirus, when we sober up to its trail of destruction in Italy and the United States, is frighteningly unbearable.