Trace the twisting course of the Orange River eastward across the face of southern Africa, and it will bring you to the roof of the sub-continent: the sandstone crests of the Maloti mountains. Rugged land of ponies and round stone cottages, the country of Lesotho (le-soo-too) possesses resources the world craves: water and clean energy. And it possesses stories. Stories born of hard times. Stories that light up the night.

Such a night was the tide of troubles that roiled southern Africa at the dawn of the 19th cent. A young warrior named Shaka had forged from his Zulu clans a fighting force without equal that sent adjoining tribes fleeing for their lives. The Basotho (the people of Lesotho) had little recourse than to run for refuge to their hills. In this flight they were led by a king named Moshoeshoe (Mo-shwe-shwe). They sought safety on a tabletop mountain with palisades on every side. There they brought their cattle, families and possessions in the hope of surviving impending siege and war. From the shadows of that time of suffering came harried souls of other clans and tribes with whom the king readily shared his retreat of last resort. That mountain refuge came to be known as Thaba Bosiu, Mountain of the Night.

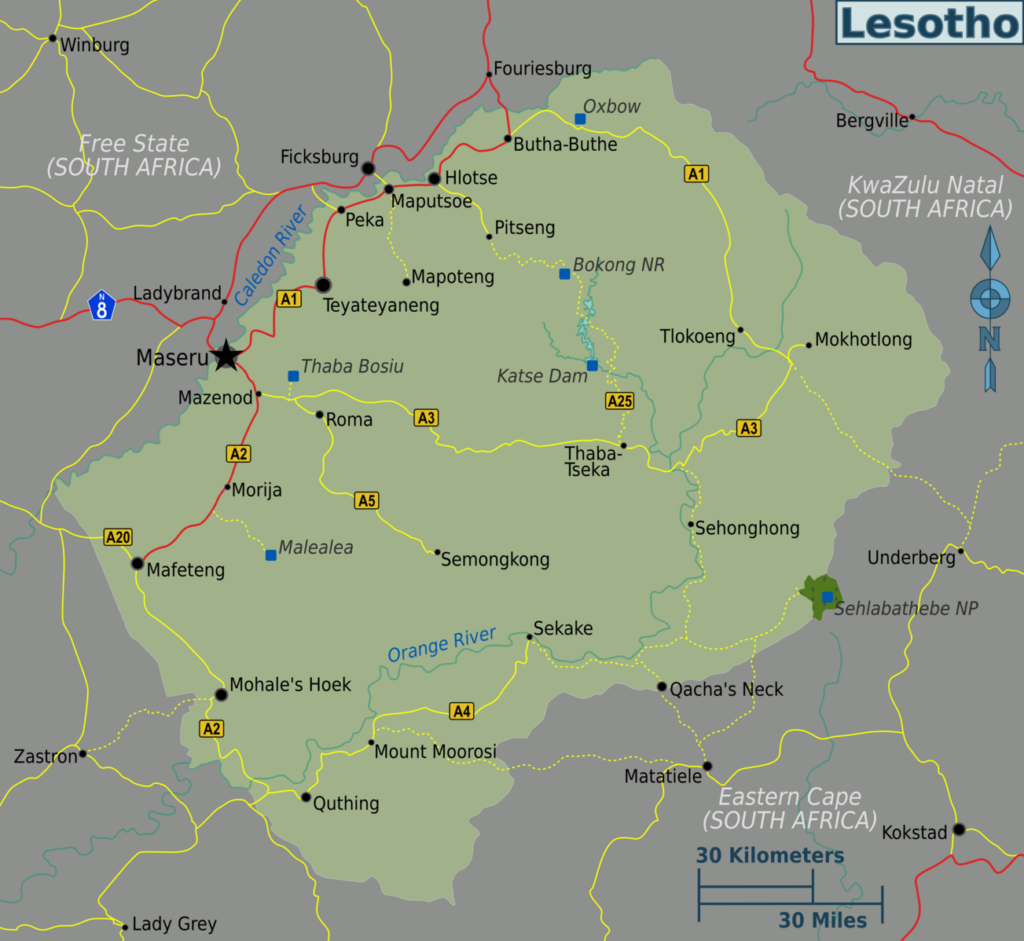

Lesotho, a little smaller than its mountain sister, Switzerland, finds itself completely surrounded by South Africa. Its survival as an independent enclave can be traced to the figure of King Moshoeshoe I who rallied his people against the pressures of the Zulu, the Xhosa, the Afrikaners and the British. The defensive advantages of the Maloti mountains helped to preserve that outcome. There remain strong cultural links with the nearby country of Botswana. The location of Thaba Bosiu appears east-southeast of the capital city, Maseru. photo credit: Peter Fitzgerald

Our visit to Thaba Bosiu reminded us of nothing so much as Masada, that mountain fastness overlooking the Dead Sea, where the remnants of a Jewish revolt held out for months against Roman legions. Unlike Masada, though, which is crowned with the ruins of palaces and fortresses, Thaba Bosiu carried only a few stone dwellings and unpretentious royal graves despite the heroics for which this place is known. Here, we were told, the Basotho grazed their herds on the mesa grasslands and sustained themselves thanks to nearby springs.

Our companion that day spared nothing in reciting the lore of this mountain. People believe, he said, that even a thimble-full of mountain dust taken home as seed for further heroics would disappear overnight, having flown back to its ridge top home. And the rumor circulated widely, especially among Moshoeshoe’s enemies, that the mountain had a way of growing at night, looming over the flatlands below.

But it was Moshoeshoe himself who rose in stature midst those troubles. Though his youth had earned him a reputation for cattle raiding and for a fiery temper, in time he was overtaken by wisdom and dignity, the makings of a mercy and peace that left a deep impression on his followers. Once during a season of starvation he was told that his own father had been taken captive, killed and, worst of all, eaten by his enemies. The cannibals were brought to the royal court for judgement and certain execution. Guilt having been established, the attendants turned to Moshoeshoe expecting a nod to make an end of this ghastly incident. But the king demurred. ‘These men’, he said, ‘having devoured my forebear have become his earthly grave. And I am duty-bound to respect his burial site. How can I desecrate it with violence?’

A modern descendant of those lofty stories, said our companion, was one day walking the streets of Soweto (South Africa) and there was accosted by an old man of regal air. He soon understood that this was the ghost of the old king, Moshoeshoe himself. The king rebuked him, demanding to know how he could walk the townships unperturbed when Lesotho, the realm of those proud stories, had been brought low by graft, violence and dishonor. So shaken was the man by this encounter, that he boarded a bus traveling straight back to Maseru, the capital. (Was he that thimble full of dust being whisked back to its true home?) There he pled with the movers and shakers of politics and of the royal house, beseeching them that the honor of their mountain past had been defiled, and that its disgrace had even stirred the shade of the old king to walk the outskirts of Johannesburg in search of some remedy. But the man’s pleas fell on deaf ears.

Not knowing what else he might do to discharge his debt to the revered king, the man climbed at evening to the top of Thaba Bosiu and laying a small pot of water on Moshoeshoe’s grave he begged forgiveness for his wayward generation, and then stood there in silent penance the whole night through. When the sun rose, he vanished.

As the story drew to a close, we stood there beside the old king’s grave, a little pot of water still upright in its place. We felt ourselves now besought by the man’s message: that however dark the shadows, there was a place of moral strength – a Thaba Bosiu – inviting us to make a nighttime stand, claiming our allegiance, seeking our answer.

Your words are full of mystery, magic, intrigue, and hope for a dark time. Thank you, Jonathan.

A most fascinating story indeed. Such legends have a way of stirring the heart.

Thank you for this story, Jonathan.

Somehow I missed your Thaba Bosiu story when you first posted it–your poetic prose is worthy of King Moshoeshoe’s moral courage. It was a gift to study the Lesotho map which you posted; during our 4 years of service with MCC in Lesotho, we visited almost every town on that map, via small plane or via 4×4 HiLux. I miss those mountains, and the people of that land. Thank you for telling a part of her story.