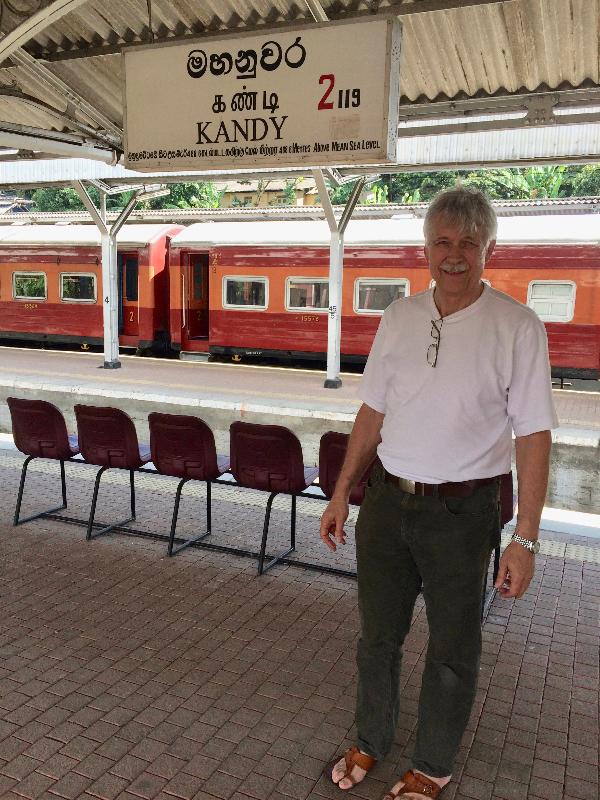

Intrigued by Daniels’ narrative, and by what if any after-story might await discovery, I set out to learn more. On a winter afternoon, 38 years after the events in the story, I boarded the afternoon train in Kandy bound for Gampola and Nawalapitiya. As I sat awaiting departure on a jewel-like day, I could imagine the figures in the story, young professionals on their eager way, Sinhalese families clad in traditional garb. The station now sported a fresh coat of paint, even a ‘clergy waiting room’ for monks, all of it a world away from that long-ago, blood-spattered afternoon. Fellow passengers seemed not to remember much of what had beset their quiet town in the ‘70s. Though all spoke with great reserve about the civil war that followed.

The winding route of the train passed tended tea bushes and shade trees shot through with sunlight, a meditation in splendor broken by the halt at Gampola. The extraordinary Sinhalese woman in the story, nameless though she remained, might very well still be out there beyond the crowded station. Imagine being raised by a woman of such moral wakefulness. Imagine the neighbors who probably knew nothing of the feat she had performed, but who believed for their own reasons she was a saint of mercy, wise beyond telling.

The train eased away bringing me presently to my destination, Nawalapitiya, hometown of the Tamil teacher. I wondered if he had told the story to his family or to neighbors, and what effect it may have had on them. But the intervening years had harrowed island communities causing many families to flee abroad. Would the story have left any traces? I had no contacts, no leads. But I had his name: J. D. Immanuel. Armed with this precious detail I set out to find a church, given this was surely a Christian surname. A short walk up a hill led me to the Anglican church where an edgy watchman told me he could offer no help and that the priest was away.

Determined not to go home empty-handed, I turned to the town library. Standing at the newspaper rack I found Mr. Nazim, an elderly Muslim who listened to my quest. He had been absent for years in the Persian Gulf, he explained, but he had many old friends in town who surely could help. Off we went on a chase through the bazaar into basement bookshops, past streetside vendors and shoe stores as a wake of curious folk gathered in our train.

But lightning grounded at a jewelry shop where the owner first asks to hear the story that has brought me so far across the sea to his doorstep. The crowd, now sprawled into the street, leans in on tiptoes as I recount the story of a resident of their town. The jeweler confesses that he doesn’t know this J. D. Immanuel, but he thinks his son might have some idea. Within minutes the son appears and reveals that he knows a member of that very family, who, summoned by cell phone, very shortly rolls up on a scooter and introduces himself as J.D. Immanuel’s half-brother, Godwin, a Pentecostal pastor.

As the scooter whisks us away, past din and diesel fumes, Godwin tells me that J.D. (John David) Immanuel passed away three years earlier, but that his son and widow still live in the region. Godwin’s children serve us tea in his modest dwelling attached to a church with only half a roof, the sheltering mango trees peering into the house. He astonishes me by saying he has never heard the story of his much older half-brother. But, he tells me, he has a story of his own.

As the fury of civil war broke upon Sri Lanka, he begins, he was a junior messenger for a corporate office in the capital. A Tamil-planted bomb exploded one day in the city center. Soon, Colombo was ruled by Sinhalese mobs driven by bloodlust. Tamil neighborhoods were set alight, vehicles torched. Police and fire services vanished as terror reigned. Bus drivers abandoned their routes. The office supervisor, fearing that Godwin’s Tamil appearance would draw mobs to his office, asked him to leave the premises. But on the streets, he would soon be prey in a pitiless jungle. He would never survive on foot the nine miles between him and his wife and three-month old child.

At that moment, a lately-hired Sinhalese woman whose name he did not know stepped forward. She told him calmly, ‘You will be my husband.” His face concealed, they set out together through a hellish scene, dodging the mobs, the flaming cars and buildings. Hours later, parched by fear and thirst, the twosome stood at his threshold where his real wife had long ago despaired of ever seeing him alive again.

“The one who owed me nothing risked her life to save mine,” muses Godwin, the Pentecostal preacher, with a faraway gaze.

I ride the bus back to Kandy in the grip of two improbable stories. It is hard to miss their resonances: moral courage from the unlikeliest quarter, emissaries of grace who remain nameless, fearless crossing of brittle social boundaries, outliers who step out of the torrent of the moment in answer to some nobler calling, radiant stories that seldom come to public notice though the atrocities hardly ever fail to appear on page one.

I have been repaid for the demands of my journey. Richly repaid. But perhaps I should have known. ‘Nawalapitiya’ means ‘town of hope’.

As always, Jonathan, so well written and the story is so beautiful and you make it come alive. Thanks for sharing you gifting of writing with us that do not have that gift. I love stories like this.

So there is a town Kandy. Love your stories. F. D. R. Summer White House, Pine Mt. Caseload at Newnan. We are back in Ind.. Jim N.

Magnificent story of grace and courage, thank you Jonathan!