Romantic love announces itself, whispers itself, in a profusion of forms: by poetry, token gift or ballad, by photographs, paisley tales, portraiture, beguiling sculpture, weavings, sometimes by regretted tattoos, or clutch of flowers, by initials notched in a handy tree or desktop, by an altogether extravagant meal. All are deeply invested signs that cannot fail to stir our depths because all are a gambit, a wild shot in the dark, an all-or-nothing wager. Something there is in us all that loves an unhedged gamble.

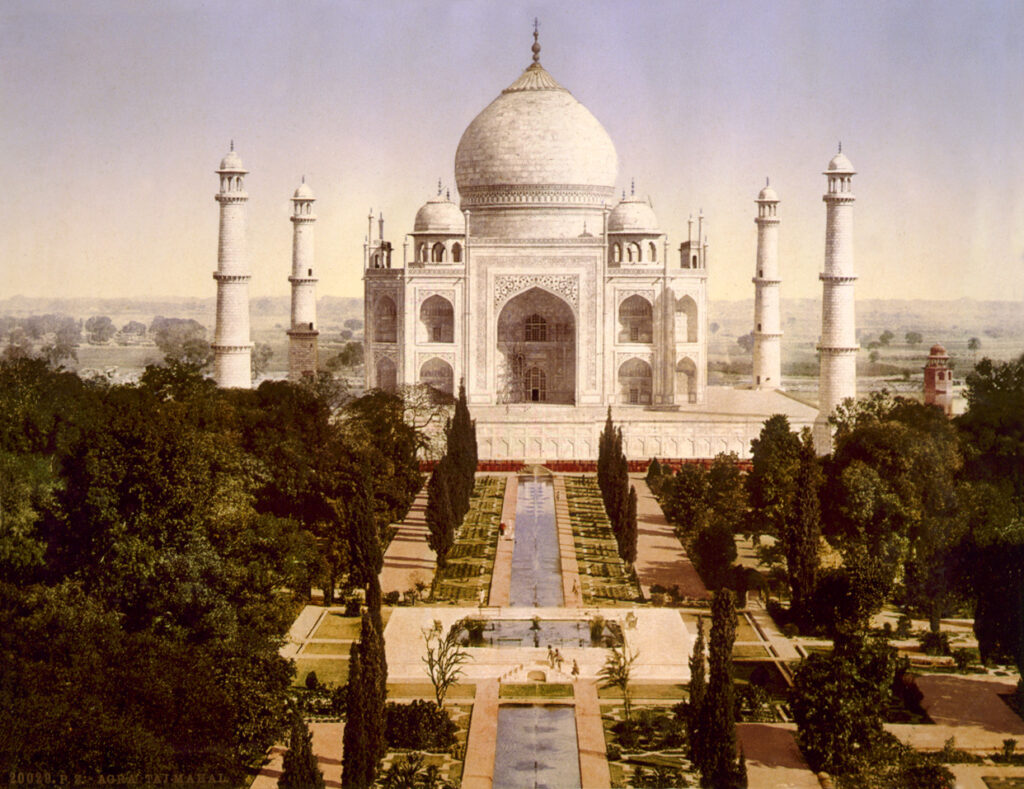

The paragon of all such monuments reigns in majesty on a storied plain beside a river sacred to the ages. It is the Taj Mahal, or, more authentically, the Mumtaz Mahal, the “palace of Mumtaz”, a sultan’s beloved consort. The love story attested by this white marble dream is rare for its time – the 17th cent. – not to say for our age that worships so readily at the altar of romantic love. That Shah Jahan, the Moghul emperor who commanded the building of this memorial, is also buried in the mausoleum is barely an afterthought. It is her name breathed by the dome, the jewel-encrusted walls, the minarets, gardens and pools.

When children we were taken to the city of Agra on the banks of the Yamuna river, as though on pilgrimage, to see this wonder, tramping through parched sandstone forts and palaces in beastly heat, captive to required stops in our education as world citizens not unlike an earlier generation of means who endured the ‘Grand Tour’ of Europe. But there was something about ‘the Taj’ which escaped me entirely until many years later when I came as an adult.

On that occasion, I excused myself from entering the cool interiors of the mausoleum, sitting instead on a retaining wall in the gardens, facing the arched entrance gates and the stream of visitors come to behold this wonder born of an ancient love that had landed itself on the global bucket list. That reverse angle on the Taj made me captive to what was reflected in the faces and demeanor of the travelers who had come to this not-to-be-missed spectacle. Many came to a standstill as they stepped into the precincts. Idle chatter fled replaced by whispers. Fumbling with handbags and purses ceased. And then began a soulful procession as visitors walked the approaches to this dream of perfect symmetry, this monument to the shattering loss of a long-ago love.

There was the turbaned Sikh with martial air, the balding grandfather and stooped wife both tapping their canes, the besotted young perhaps on a honeymoon, the bare-foot farmer in traditional dhoti, his wife in a fuschia sari a few dutiful steps behind, a gaggle of schoolchildren in jeans and halter tops, a middle-aged woman alone with barely restrained tears, the nun in starched habit, monks in maroon and saffron robes, students in stylish sneakers with backpacks, spiritual seekers in rough cotton and sandals, a young mother nursing an infant as she dreams for her child, and the well-heeled tourists slung with cameras, but now limping for the blisters sustained from their exertions.

A flock of parakeets roused me from this reverie. And then it dawned for me that this was its own monument to love: a stream of humble practitioners, of pilgrims, who had come seeking a reminder of the nobility, the self-forgetfulness, the fragile beauty of enduring love, a love visible in the weathered, everyday faces of the throng. That throng had somewhere built its own Taj, however modest, or at least dreamed of such an edifice.

Shah Jahan, the bereaved sultan, could have retained no architect so deft as to capture such a vision of love as belongs to the likes of you and me.

The Taj Mahal was my first beacon from a world beyond my own. My 4th grade teacher, Mrs. Jo Scott, showed our little class in Fairbanks, Alaska film projector photos of this testament to love, and I vowed to see it for myself someday. That has not (yet) happened! Thank you for sharing your story of encountering its beauty.

I read this responsive reading that you sent us this morning. It really was a meaningful service. Still like to see you again sometime but maybe I’ll have to be later. We have that hope of meeting again. We also showed your picture that you have here.